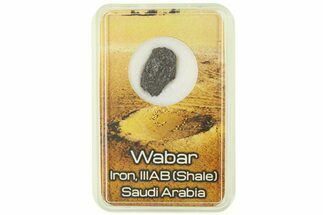

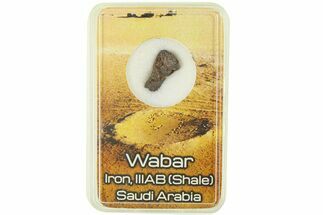

.35" Oxidized Meteorite (IIIAB) Fragment (0.57 g) - Wabar

This is a .35" wide (0.57 gram) piece of the Wabar iron meteorite from the famous craters of Saudi Arabia's desolate Rub'al Khali desert. It comes with the pictured acrylic display case.

Wabar is an iron (IIIAB) meteorite found in eastern Saudi Arabia. They were first knwon in the West when British explorer Harry St John Philby stumbled upon the craters in 1932 in the large stretch of open desert known locally as Rub'al Khali. He was searching for the mythical city of Ubar, mentioned in the Quran, when he found three large craters containing white sandstone impactites, black impact glass, and iron meteorites. Local Bedouin groups had referred to the craters as Al Hadida, or "place of iron", and had reported finding iron masses the size of camels in the area. At first St John Philby thought he found an ancient volcano, but the samples he brought back to England were verified as meteorites.

The Wabar meteorite itself likely fell sometime during the 19th century, consistent with some eyewitness accounts from Arab communities in 1863 or 1891. The area is now largely inaccessible due to the sheer harshness and desolation of the area, regional political instability, and the slow march of sand as it has filled in the craters themselves. As such, material can no longer be collected from the site.

Though material can no longer be collected, collectors can find a great deal of interesting specimens from the site. Black glass impactites, known as Wabar pearls, can be frequently found, as well as fresh or oxidized fragments of meteorite. Sliced and etched meteorite specimens often display fine Widmanstätten patterns.

The Wabar meteorite itself likely fell sometime during the 19th century, consistent with some eyewitness accounts from Arab communities in 1863 or 1891. The area is now largely inaccessible due to the sheer harshness and desolation of the area, regional political instability, and the slow march of sand as it has filled in the craters themselves. As such, material can no longer be collected from the site.

Though material can no longer be collected, collectors can find a great deal of interesting specimens from the site. Black glass impactites, known as Wabar pearls, can be frequently found, as well as fresh or oxidized fragments of meteorite. Sliced and etched meteorite specimens often display fine Widmanstätten patterns.

About Iron Meteorites

Iron type meteorites are composed primarily of iron and nickel, and are the remnants of differential cores torn apart at the beginning of the solar system. These metallic meteorites are often the easiest to identify after millions of years post-impact because they are quite different from terrestrial material, especially when it comes to their mass-to-surface area ratio. They are exceptionally heavy for their size since iron is a high-density metal: this is also why the Earth's core is nickel-iron. As planets form, the densest metals form gravitational centers, bringing more and more material into their gravitational pull. In the solar system's rocky planets, these dense materials are most often nickel and iron.

Most iron meteorites have distinctive, geometric patterns called Widmanstätten patterns, which become visible when the meteorite is cut and acid etched. These patterns are criss-crossing bands of the iron-nickel alloys kamacite and taenite that slowly crystalized as the core of the meteorites' parent bodies slowly cooled. Such large alloy crystallizations for mover millions of years and do not occur naturally on Earth, further proving that iron meteorites come from extraterrestrial bodies.

Iron type meteorites are composed primarily of iron and nickel, and are the remnants of differential cores torn apart at the beginning of the solar system. These metallic meteorites are often the easiest to identify after millions of years post-impact because they are quite different from terrestrial material, especially when it comes to their mass-to-surface area ratio. They are exceptionally heavy for their size since iron is a high-density metal: this is also why the Earth's core is nickel-iron. As planets form, the densest metals form gravitational centers, bringing more and more material into their gravitational pull. In the solar system's rocky planets, these dense materials are most often nickel and iron.

Most iron meteorites have distinctive, geometric patterns called Widmanstätten patterns, which become visible when the meteorite is cut and acid etched. These patterns are criss-crossing bands of the iron-nickel alloys kamacite and taenite that slowly crystalized as the core of the meteorites' parent bodies slowly cooled. Such large alloy crystallizations for mover millions of years and do not occur naturally on Earth, further proving that iron meteorites come from extraterrestrial bodies.

$53

TYPE

Iron (Fine Octahedrite, IIIAB)

AGE

LOCATION

Rub'al Khali, Saudi Arabia

SIZE

.35" wide, Weight: 0.57 grams

CATEGORY

ITEM

#286061

Reviews

Reviews