This Specimen has been sold.

6" Plate Jimbacrinus Crinoid Fossils - Australia (Special Price)

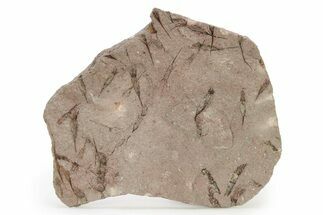

This is beautiful mortality plate of Jimbacrinus bostocki crinoid fossils from Western Australia with five individuals on it. These crinoids are 3D and have a very alien appearance. The plate is 6x4.6" and has been nicely prepared. The largest crinoid on this plate measures 2.3" long.

These Jimbacrinus crinoids are hard to acquire due to Australia's strict fossil export laws. This specimen was exported legally during the 80's and was in a collection for year before being recently re-prepared.

These Jimbacrinus crinoids are hard to acquire due to Australia's strict fossil export laws. This specimen was exported legally during the 80's and was in a collection for year before being recently re-prepared.

Jimbacrinus bostocki, found in Western Australia, is a very popular crinoid on the fossil market. With its large, bumpy calyx, feathery arms, and long, thick stalk, it makes for quite the attractive display. As far as crinoids go, they’re extremely well preserved with excellent detail and have a tan-brown coloring that contrasts nicely with the rich red rock they are found in. The feathery pinnules of J. bostocki are exceptionally preserved, which is one of the main reasons why it is such a highly sought fossil. They can also be rather large for a crinoid, with crowns reaching lengths of 9 inches.

Crinoids are a type of echinoderm related to starfish and sea cucumbers. There are roughly 600 living crinoid species anchored in the world’s oceans, progeny of the survivors of the Permian-Triassic extinction. Since their origins 300 million years ago, crinoids have kept the same basic body plan (one of the premier examples of the saying, “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it”).

Jimbacrinus crinoids lived on the Permian seafloor some 280 million years ago. They lived a rather sessile life tethered to the seafloor, filter feeding on any plankton that drifted by. All crinoids have the same basic body plan: a long, flexible stalk/tether allows the crinoid to anchor themselves to the seafloor. Their main body, called the calyx, resembles a misshapen sphere and is made up of very small plates of calcite that allow them to maintain rigidity. The calyx is where the major organs were contained, including the anus and the mouth. Extending off of the calyx are the arms, of which J. bostocki had five. Each arm was lined with feather-like pinnules that they used to filter the ocean water for particulates and detritus.

These Western Australian crinoids are increasingly difficult to find, since the best source is a river bed that undergoes frequent cycles of intense flooding and extreme desiccation. Originally discovered in 1949 in the Gascoyne Junction, part of the Cundlego Formation, it is part of an excellent index of species that died off at the boundary between the Permian and the Triassic. This time period was one of the largest extinction events in natural history, with an estimated loss of 90% of the marine species at the time. A global temperature increase that acidified the oceans and starved the occupants of oxygen is the likely cause of this mass die-off. As it stands, Jimbacrinus bostocki has not been found outside of the Cundlego Formation.

A video by Tom Kapitany showing the location where he collects these Jimbacrinus crinoids in Australia.

Crinoids are a type of echinoderm related to starfish and sea cucumbers. There are roughly 600 living crinoid species anchored in the world’s oceans, progeny of the survivors of the Permian-Triassic extinction. Since their origins 300 million years ago, crinoids have kept the same basic body plan (one of the premier examples of the saying, “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it”).

Jimbacrinus crinoids lived on the Permian seafloor some 280 million years ago. They lived a rather sessile life tethered to the seafloor, filter feeding on any plankton that drifted by. All crinoids have the same basic body plan: a long, flexible stalk/tether allows the crinoid to anchor themselves to the seafloor. Their main body, called the calyx, resembles a misshapen sphere and is made up of very small plates of calcite that allow them to maintain rigidity. The calyx is where the major organs were contained, including the anus and the mouth. Extending off of the calyx are the arms, of which J. bostocki had five. Each arm was lined with feather-like pinnules that they used to filter the ocean water for particulates and detritus.

These Western Australian crinoids are increasingly difficult to find, since the best source is a river bed that undergoes frequent cycles of intense flooding and extreme desiccation. Originally discovered in 1949 in the Gascoyne Junction, part of the Cundlego Formation, it is part of an excellent index of species that died off at the boundary between the Permian and the Triassic. This time period was one of the largest extinction events in natural history, with an estimated loss of 90% of the marine species at the time. A global temperature increase that acidified the oceans and starved the occupants of oxygen is the likely cause of this mass die-off. As it stands, Jimbacrinus bostocki has not been found outside of the Cundlego Formation.

A video by Tom Kapitany showing the location where he collects these Jimbacrinus crinoids in Australia.

SPECIES

Jimbacrinus bostocki

LOCATION

Gascoyne Junction, Western Australia

FORMATION

Cundlego Formation

SIZE

Matrix 6x4.6", Largest crinoid 2.3"

CATEGORY

SUB CATEGORY

ITEM

#68357

We guarantee the authenticity of all of our specimens.

Reviews

Reviews