About Allosaurus

Allosaurus

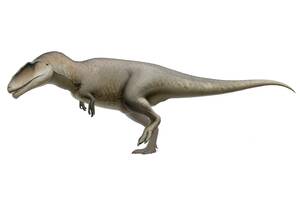

was a theropod of the Late Jurassic that lived from 156 to 145 million years ago. It was a predator with a massive skull, serrated teeth, and gaping jaws. Allosaurus had brow horns which appear to have varied somewhat in shape between individuals. This powerful and plentiful carnivore genus could grow to almost 39 feet long.

The abundance of Allosaurus skeletons has provided scientists with evidence to propose behavior. Allosaurus may have used hunting strategies such as flesh grazing, pack hunting, and ambush attacks that utilized trachea crushing bites. It likely grasped its meal with its legs and mouth and pulled its meal apart. Its unusual gaping jaw has spurred debate regarding Allosaurus using its head like a hatchet to attack and slice at prey. There is also taxonomic controversy regarding what species belong to Allosaurus.

In Greek, Allosaurus means “different lizard.”

Allosaurus could grow 39 feet long, perhaps even longer.

Allosaurus was a carnosaurian theropod, not a tyrannosauroid.

Allosaurus is more commonly found in North America, Portugal, and Tanzania.

Allosaurus was an apex predator. Debate continues regarding how it may have killed much larger prey.

The social behavior of Allosaurus is unclear. Fossils reveal a life of physical trauma.

Allosaurus fossils are the most abundant of the large predators in the Morrison Formation.

Allosaurus was designated as the state fossil of Utah in 1988.

Allosaurus had an average length of 28 ft (8.5m), though some fossils suggest Allosaurus could be as long as 39 ft. (12 m). The longest conclusive specimen of Allosaurus is 32 ft long. This specimen is believed to have weighed 2.5 short tons (2.3 metric tonnes), though weight estimates for Allosaurus vary greatly. John Foster uses his familiarity with fossilized thigh bones to report a reasonable estimate for a large A. fragilis as 2200 lbs (1000 kg). He suggests that 1500 lbs (700 kg) could be the weight of an average-sized Allosaurus. Researchers modeled a sub-adult called “Big Al”. They concluded that an adult would weigh 3,300 lbs (1500 kg), though a range between 3100-4400 lbs (1400 kg- 2000 kg) was produced when parameters were varied.

In the past, specimens of the genus Saurophaganax have been referred to as members of the Allosaurus genus. Saurophaganax was estimated to be 36 ft long (10.9 m) and new research asserts its placement as a separate genus. Epanterias was a species estimated to be 40 ft long and belonging to the Allosaurus genus. Remains found in New Mexico at the Peterson Quarry, suggest that Epanterias may actually be Saurophaganax. Taxonomic distinctions within Allosaurus are continually investigated.

The Allosaurus tail was long and muscular, the neck was short, and the skull was very large. The neck had nine vertebrae. The number of tail vertebrae may have varied with size. Different estimations suggest there were less than 45 tail vertebrae, and as many as 50. Allosaurus had 14 back vertebrae and 5 sacral vertebrae. Vertebrae of the neck and at the anterior of the back contained hollow spaces, which like modern birds, may have been air sacs that were part of the respiratory system.

Allosaurus was barrel-chested and had belly ribs, called gastralia, which may typically be poorly preserved. Allosaurus also had a furcula, or wishbone. Allosaurus had a large hip bone (illium). The pubic bone had a projection described as a foot. This “foot” may have assisted the animal when it sat on the ground, or it could have been for muscle attachment. Specimens found at The Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry have revealed that only about half of the specimens found there have pubic bones that fused at the foot ends. The fusion is not size dependent. Scientist Madsen suggests that the lack of fusion may indicate a trait of the female and may be associated with egg-laying.

Allosaurus had powerful but relatively small forelimbs, each with three, curved claws. It had a characteristic semilunate carpal which continued to evolve in later theropods. The innermost digit consisted of 2 phalanges, the middle digit had 3, and the third digit had 4 phalanges. The ‘thumb’ was the largest of the three fingers. Claws of the feet were more hoof-like than more ancestral theropods. The toes were weight-bearing, the foot had a dewclaw, and the remnants of a fifth metatarsal may have been associated with the Achilles tendon. James Madsen submits that juveniles may have used the dewclaw for grasping.

G.S. Paul calculates a skull length of 33.3 in for a 26 ft.-long Allosaurus. The maxilla contained 14-17 teeth, the premaxilla held five, and the lower jar (dentary) held 14-17 teeth. Allosaurus had D-shaped teeth which progressively narrowed, shortened, and became more curved as they grew from the back of the mouth. Allosaurus teeth had saw-like, serrated edges and were continually shed and replaced.

The Allosaurus skull has unique traits. Allosaurus had extensions on its lacrimal bones which formed a brow horn over each eye. These horns varied somewhat in shape and size. Low ridges extended from them along nasal bones. Some theories on the purpose of the horns include display, weapons for combat, and possibly as effective sunshades. These horns, likely covered in keratin, are believed to have been fragile. Like some tyrannosaurids, the skull roof contained a ridge for muscle attachment. Unlike the leg bones, the skull grew in an isometric manner (proportions were maintained as the animal got bigger).

The lacrimal bones have shallow pits that suggest a place for glands. The maxillae contained sinuses that may have held a sensory organ similar to the Jacobson’s organ or another organ associated with the ability to smell. Allosaurus may have used a thin braincase to facilitate thermoregulation. Allosaurus had jaws which could gape very wide. It had loose articulation between the halves of the front and back lower jaws. This created a bowing effect, which permitted the wider gape. There is also a possible joint of the frontals and braincase.

A CT scanned endocast of Allosaurus leads scientists to conclude that the Allosaurus brain shares greater similarity with crocodiles than with living birds. The skull was held horizontally, and the inner ear structure was also like that of a crocodile. This suggests that Allosaurus was probably most sensitive to lower frequencies. Large olfactory bulbs would have facilitated the detection of smells, though the locales associated with evaluating odors were relatively reduced.

Allosaurus likely ate large herbivores such as ornithopods, sauropods, and stegosaurs. Fossil evidence has displayed scrapes and bite marks on sauropods and stegosaurs which match Allosaurus. The marks display evidence that Allosaurus would have hunted the live animals, and scavenged them, as well. In 1988, G. Paul asserted that unless Allosaurus was a pack hunter, it was probably unable to take down a fully grown sauropod. Instead, Allosaurus may have focused the hunt on juvenile prey. Paul notes that the comparably modest skull and small teeth would not have been adequate for hunting enormous prey. R.T Bakker proposes that Allosaurs used its saw-like teeth, gaping jaw, and strong neck muscles to slash its prey. Such attacks would weaken the victim.

Biochemical studies on the Allosaurus skull revealed that the bite force was less than that of lions, or even leopards. The calculations estimate a maximum bite force for Allosaurus to be 2.148 N, while a leopard exceeds that with a bite force of 2,268 N. The tooth row of the skull, however, could withstand a much greater vertical force of 55,000 N. This detail promotes the idea that Allosaurus used its skull like a hatchet against large prey and slashed with the serrated teeth. The skull was adequately light and strong to attack both agile small prey and large herbivores.

Theories about feeding strategy are still under investigation. Challengers to the hatchet theory remark on the lack of modern comparisons and explain that such adaptations of the Allosaurus skull were suited to withstand the forces of struggling prey. The supporters of the hatchet strategy cite their opponent’s observations regarding skull articulation as reasons why such traits would decrease stress, protect the palate, and support the hatchet-like attack. An alternative feeding strategy proposes that Allosaurus grazed the flesh of large prey, taking bites from the living animal and leaving the giant beasts to survive as another future meal. Another possible strategy is that Allosaurus used strong forelimbs to grasp prey as cats do, and then crushed the trachea with repeated bites.

In 2013, Snively and others found a place on the skull where a neck muscle attached in a lower place than it did for Tyrannosaurs and other theropods. Such a trait would have allowed Allosaurus to make quick, powerful vertical motions with its skull. Scientists propose that Allosaurus grasped prey with its mouth and feet. The Allosaurus then pulled back and up, removing flesh in a similar manner as falcons. Other theropods are believed to have used their jaws more like a crocodile. In the Allosaurus, power seems to have been sacrificed for mobility of the head and neck.

The binocular vision of Allosaurus probably did not exceed a width of 20°. This is due to skull shape. The range is less wide than living crocodiles, though sufficient to judge the distance of prey. Such biological clues suggest that Allosaurus may have utilized an ambush strategy. The claws appear to have been utilized as hooks, and the arms could clutch things closely, or reach and grasp. The maximum speed of Allosaurus is estimated to be 19-34 mph (30-55 km/hr).

Allosaurus is proposed to have had cooperative social behavior, such as hunting in packs. However, there scant evidence to support this idea. Some scientists explain that groups of Allosaurus fossils are together because of aggressive behavior or that individuals were eating the same kill. Bakker suggests that adults may have brought food to their young. While pack hunting and gregarious behavior has been suggested, injured gastralia and bites to the skull suggest that interactions among Allosaurus were antagonistic.

Arguments against cooperative behavior assert that vertebrates rarely cooperatively hunt to bring down very large prey, and that animals like crocodiles and birds do not typically hunt in such a manner. In fact, such animals typically cannibalize and attack smaller members of their species when they are gathered to feed. Fossil allosaurs at the Cleveland-Lloyd quarry and at feeding sites studied by Bakker reveal a high number of juvenile and subadult deaths. This proportion is also observed among crocodiles and Komodo dragons. There is fossil evidence suggesting that Allosaurus cannibalized each other.

Tendon avulsions of the forelimbs suggest injuries to Allosaurus occurred while they held struggling prey. Injuries to the feet occurred not from running, but likely from grasping struggling animals with the feet. Such injuries suggest a diet based on active predation.

Fossil remains reveal a highest rate of growth at 15 years old, and bone deposition halted between 22 and 28 years old. Medulary bone tissue has been found in Allosaurus. This tissue is used to produce calcium for eggshells, is found in female birds, and suggests a way to identify the females of Allosaurus. Another possibility is that medulary bone found in Allosaurus might be a remnant of bone pathology.

Juveniles had longer legs compared to their adult proportions. Such a trait may have allowed different hunting strategies than they would have employed as massive adults. The total length of the shin and foot exceeded that of the thigh, allowing Allosaurus to run effectively. Juveniles may have chased down small prey. As the thigh bone thickened and widened, the muscles also became shorter. Growth slowed in the adult. These changes suggest that the legs of the adults endured significantly more stress than the juveniles.

The Jurassic Period is from 201.3-145 mya, and began after the Jurassic-Triassic extinction event. The supercontinent Pangaea rifted into Laurasia and Gondwana. The North Atlantic opened during the Jurassic, but it wasn’t until the Cretaceous that Gondwana rifted to open the South Atlantic Oceans. The Nevadan orogeny, caused by a subduction zone, began in the mid-Jurassic. Intrusive batholiths associated with extrusive volcanoes are seen today as exposures in the Sierra Nevada Mtns. In the modern North American west, the banded and colorful remnants of the Morrison Formation are exposed in arid and often remote locales.

In the Jurassic, more coastlines formed, continental climate became more humid, and dinosaurs began to dominate the land over the descendents of Triassic crocodylomorphs. Birds evolved from theropods, crocodylians filled aquatic niches, and marine reptiles populated the oceans.

Allosaurus is found in western North America, within the Morrison Formation. The formation records semi-arid floodplains and forests which lined rivers. There were wet and dry seasons. Forests were populated by conifers, ferns, and tree ferns. Savannas were also dominated by ferns and a rare conifer called a Brachyphyllum. Allosaurus lived at the apex of the trophic levels, and is the most common theropod found in the Morrison.

The Morrison Fm. has preserved many organisms from the Jurassic. Fungi, mosses, horsetails, cycads, and ginkos grew, in addition to many species of conifers. Ray-finned fish, turtles, lizards, crocodylomorphs, pterosaurs, early mammals, and many dinosaurs lived at that time. Allosaurus is frequently buried in the same area as Apatosaurus (sauropod), Camarasaurus (sauropod), and Stegasaurus (ornithiscian). Theropods of the Morrison include Ceratosaurus, Torvosaurus, Ornitholestes. Sauropods also include Brachiosaurus and Diplodocus. Ornithscians also include Camptosaurus and Dryosaurus.

In the U.S. and Portugal theropods occupied different niches. Fossil remains and geology provide clues to how Allosaurus lived with Ceratosaurus and Torvosaurus. Ceratosaurus and Torvosaurus had thinner bodies that suggest they were built for living in the forest and underbrush around waterways. Allosaurs had longer legs and are typically associated with floodplains. Functional anatomy differed among these species, as well. Fossil evidence reveals that Allosaurus was eaten by bigger carnivores scavenging a dead Allosaurus.

The first recorded discovery of an Allosaurus fossil was in 1869, likely retrieved from Morrison Formation strata near Granby, CO. Leidy received the piece of tail vertebrae from F.V. Hayden who acquired the fossil secondhand. The fossil was first assigned to a European genus, but Leidy eventually assigned it to Antrodemus. In 1877, O.C. Marsh named Allosaurus fragilis. The Greek meaning of Allosaurus is ’different lizard.’ The vertebral fragments from the collection which Marsh studied had features which made the vertebrae lighter, hence the epithet, ‘fragilis’. Marsh continued to competitively collect and name theropod specimens, as did his rival E.D. Cope. In 1920, C.W. Gilmore asserted that Leidy’s Antrodemus vertebrae appeared the same as Allosaurus, therefore Antrodemus should be the accepted name. Madsen published his argument that Antrodemus was inadequately identified and named, and that Allosaurus should be the name used.

The Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry has been collected since 1927, described in 1945, and has been a focus of major academic study and collection since the 1960’s. At least 73 dinosaurs have been extracted, with at least 46 of those identified as Allosaurus fragilus. Individuals range in size from one to twelve meters long. The specimens are notably disarticulated and the circumstance of their burial in such large quantity is unresolved. Some of the explanations are that the animals got stuck in the mud, a bog, or a seep, and/or that drought brought the dinosaurs to a waterhole where they died.

In 1991, a Swiss team discovered a 95% complete, 26 ft (8 m) long Allosaurus skeleton near Shell, Wyoming. The skeleton (MOR 693) was named “Big Al.” “Big Al” has received considerable popular recognition. The Swiss team also discovered one of the best preserved specimens of Allosaurus. They found it in 1996 and nicknamed it “Big Al Two.” “Big Al”, described by Breithaupt, had 19 bones with pathology such as breaks and bones infections (osteomyelitis).

The taxonomy of the Allosaurus genus is very complicated due to the fragmentary nature of the type specimen (A. fragilis). In 1877, O.C. Marsh described the first known fossils of this genus, though the fossils were called Antrodemus. Before 1976, publications described Allosaurus as Megalauridae and Antrodremus. Many other theropod dinosaurs were assigned to Allosauridae and have since been moved to different families. A petition was submitted in 2010 to have A. fragilis transferred to a more complete, neotype specimen.

Allosaurus is a carnosaur, which is a separate branch of theropods from the tyrannosaurids. Tyrannosaurids belong to Coelosauria. Allosauridae has the fewest members of the four families within Carnosauridae. Members include Allosaurus, Saurophaganax (which may be an Allosaurus), and possibly members of the genus, Epanterias. Some scientists assert that Epanterias is a member of Allosauridae, but Saurophaganax belongs in a separate genus.

Since 1988, seven species have been asserted as most correctly belonging to Allosaurus, as well as ten more which are assigned but their placement is contested. Most assignments to Allosaurs have been contested, a situation caused by the meager example of bones associated with the type specimen. In addition, other genera have been added to Allosaurus. These classifications have made Allosaurus somewhat of a catch-all for Allosaurus-like, tetanuran theropods. Tetanurae was proposed by J. Gauthier, in 1986. Members of Tetanurae appear in the early to middle Jurassic, and include Carnosauridae and Coelosauridae, and they share closer relationships to birds than to Ceratosaurus.

The most common Allosaurus found in the Upper Jurassic of North America is A. fragilis. Other species that have been discovered from the same formation are A. maximus and A. jimmadseni. Scientists have debated whether the only two described species of the Morrison are A. fragilis and the taxonomically disputed, A. atrox. The possibility remains that Allosaurus in the Morrison includes only one species and individual variation explains the differences observed among specimens. Skulls from the Cleveland-Lloyd quarry have revealed that species distinction based on lacrimal horns and jugal shape may be an incorrect approach.

There are other notable members of Allosaurus which are outside of North America. Allosaurus europaeus was discovered in Late Jurassic sediments of western Portugal. This species may also be A. fragilis. A large theropod, possibly a basal tetanuran or carcharodontosaurid, is found in Tanzania and is classified as A. tendagurensis.

The abundance of Allosaurus skeletons has provided scientists with evidence to propose behavior. Allosaurus may have used hunting strategies such as flesh grazing, pack hunting, and ambush attacks that utilized trachea crushing bites. It likely grasped its meal with its legs and mouth and pulled its meal apart. Its unusual gaping jaw has spurred debate regarding Allosaurus using its head like a hatchet to attack and slice at prey. There is also taxonomic controversy regarding what species belong to Allosaurus.

Size

Allosaurus had an average length of 28 ft (8.5m), though some fossils suggest Allosaurus could be as long as 39 ft. (12 m). The longest conclusive specimen of Allosaurus is 32 ft long. This specimen is believed to have weighed 2.5 short tons (2.3 metric tonnes), though weight estimates for Allosaurus vary greatly. John Foster uses his familiarity with fossilized thigh bones to report a reasonable estimate for a large A. fragilis as 2200 lbs (1000 kg). He suggests that 1500 lbs (700 kg) could be the weight of an average-sized Allosaurus. Researchers modeled a sub-adult called “Big Al”. They concluded that an adult would weigh 3,300 lbs (1500 kg), though a range between 3100-4400 lbs (1400 kg- 2000 kg) was produced when parameters were varied.

In the past, specimens of the genus Saurophaganax have been referred to as members of the Allosaurus genus. Saurophaganax was estimated to be 36 ft long (10.9 m) and new research asserts its placement as a separate genus. Epanterias was a species estimated to be 40 ft long and belonging to the Allosaurus genus. Remains found in New Mexico at the Peterson Quarry, suggest that Epanterias may actually be Saurophaganax. Taxonomic distinctions within Allosaurus are continually investigated.

Anatomy

The Allosaurus tail was long and muscular, the neck was short, and the skull was very large. The neck had nine vertebrae. The number of tail vertebrae may have varied with size. Different estimations suggest there were less than 45 tail vertebrae, and as many as 50. Allosaurus had 14 back vertebrae and 5 sacral vertebrae. Vertebrae of the neck and at the anterior of the back contained hollow spaces, which like modern birds, may have been air sacs that were part of the respiratory system.

Allosaurus was barrel-chested and had belly ribs, called gastralia, which may typically be poorly preserved. Allosaurus also had a furcula, or wishbone. Allosaurus had a large hip bone (illium). The pubic bone had a projection described as a foot. This “foot” may have assisted the animal when it sat on the ground, or it could have been for muscle attachment. Specimens found at The Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry have revealed that only about half of the specimens found there have pubic bones that fused at the foot ends. The fusion is not size dependent. Scientist Madsen suggests that the lack of fusion may indicate a trait of the female and may be associated with egg-laying.

Allosaurus had powerful but relatively small forelimbs, each with three, curved claws. It had a characteristic semilunate carpal which continued to evolve in later theropods. The innermost digit consisted of 2 phalanges, the middle digit had 3, and the third digit had 4 phalanges. The ‘thumb’ was the largest of the three fingers. Claws of the feet were more hoof-like than more ancestral theropods. The toes were weight-bearing, the foot had a dewclaw, and the remnants of a fifth metatarsal may have been associated with the Achilles tendon. James Madsen submits that juveniles may have used the dewclaw for grasping.

G.S. Paul calculates a skull length of 33.3 in for a 26 ft.-long Allosaurus. The maxilla contained 14-17 teeth, the premaxilla held five, and the lower jar (dentary) held 14-17 teeth. Allosaurus had D-shaped teeth which progressively narrowed, shortened, and became more curved as they grew from the back of the mouth. Allosaurus teeth had saw-like, serrated edges and were continually shed and replaced.

The Allosaurus skull has unique traits. Allosaurus had extensions on its lacrimal bones which formed a brow horn over each eye. These horns varied somewhat in shape and size. Low ridges extended from them along nasal bones. Some theories on the purpose of the horns include display, weapons for combat, and possibly as effective sunshades. These horns, likely covered in keratin, are believed to have been fragile. Like some tyrannosaurids, the skull roof contained a ridge for muscle attachment. Unlike the leg bones, the skull grew in an isometric manner (proportions were maintained as the animal got bigger).

The lacrimal bones have shallow pits that suggest a place for glands. The maxillae contained sinuses that may have held a sensory organ similar to the Jacobson’s organ or another organ associated with the ability to smell. Allosaurus may have used a thin braincase to facilitate thermoregulation. Allosaurus had jaws which could gape very wide. It had loose articulation between the halves of the front and back lower jaws. This created a bowing effect, which permitted the wider gape. There is also a possible joint of the frontals and braincase.

A CT scanned endocast of Allosaurus leads scientists to conclude that the Allosaurus brain shares greater similarity with crocodiles than with living birds. The skull was held horizontally, and the inner ear structure was also like that of a crocodile. This suggests that Allosaurus was probably most sensitive to lower frequencies. Large olfactory bulbs would have facilitated the detection of smells, though the locales associated with evaluating odors were relatively reduced.

Feeding

Allosaurus likely ate large herbivores such as ornithopods, sauropods, and stegosaurs. Fossil evidence has displayed scrapes and bite marks on sauropods and stegosaurs which match Allosaurus. The marks display evidence that Allosaurus would have hunted the live animals, and scavenged them, as well. In 1988, G. Paul asserted that unless Allosaurus was a pack hunter, it was probably unable to take down a fully grown sauropod. Instead, Allosaurus may have focused the hunt on juvenile prey. Paul notes that the comparably modest skull and small teeth would not have been adequate for hunting enormous prey. R.T Bakker proposes that Allosaurs used its saw-like teeth, gaping jaw, and strong neck muscles to slash its prey. Such attacks would weaken the victim.

Biochemical studies on the Allosaurus skull revealed that the bite force was less than that of lions, or even leopards. The calculations estimate a maximum bite force for Allosaurus to be 2.148 N, while a leopard exceeds that with a bite force of 2,268 N. The tooth row of the skull, however, could withstand a much greater vertical force of 55,000 N. This detail promotes the idea that Allosaurus used its skull like a hatchet against large prey and slashed with the serrated teeth. The skull was adequately light and strong to attack both agile small prey and large herbivores.

Theories about feeding strategy are still under investigation. Challengers to the hatchet theory remark on the lack of modern comparisons and explain that such adaptations of the Allosaurus skull were suited to withstand the forces of struggling prey. The supporters of the hatchet strategy cite their opponent’s observations regarding skull articulation as reasons why such traits would decrease stress, protect the palate, and support the hatchet-like attack. An alternative feeding strategy proposes that Allosaurus grazed the flesh of large prey, taking bites from the living animal and leaving the giant beasts to survive as another future meal. Another possible strategy is that Allosaurus used strong forelimbs to grasp prey as cats do, and then crushed the trachea with repeated bites.

In 2013, Snively and others found a place on the skull where a neck muscle attached in a lower place than it did for Tyrannosaurs and other theropods. Such a trait would have allowed Allosaurus to make quick, powerful vertical motions with its skull. Scientists propose that Allosaurus grasped prey with its mouth and feet. The Allosaurus then pulled back and up, removing flesh in a similar manner as falcons. Other theropods are believed to have used their jaws more like a crocodile. In the Allosaurus, power seems to have been sacrificed for mobility of the head and neck.

The binocular vision of Allosaurus probably did not exceed a width of 20°. This is due to skull shape. The range is less wide than living crocodiles, though sufficient to judge the distance of prey. Such biological clues suggest that Allosaurus may have utilized an ambush strategy. The claws appear to have been utilized as hooks, and the arms could clutch things closely, or reach and grasp. The maximum speed of Allosaurus is estimated to be 19-34 mph (30-55 km/hr).

Behavior

Allosaurus is proposed to have had cooperative social behavior, such as hunting in packs. However, there scant evidence to support this idea. Some scientists explain that groups of Allosaurus fossils are together because of aggressive behavior or that individuals were eating the same kill. Bakker suggests that adults may have brought food to their young. While pack hunting and gregarious behavior has been suggested, injured gastralia and bites to the skull suggest that interactions among Allosaurus were antagonistic.

Arguments against cooperative behavior assert that vertebrates rarely cooperatively hunt to bring down very large prey, and that animals like crocodiles and birds do not typically hunt in such a manner. In fact, such animals typically cannibalize and attack smaller members of their species when they are gathered to feed. Fossil allosaurs at the Cleveland-Lloyd quarry and at feeding sites studied by Bakker reveal a high number of juvenile and subadult deaths. This proportion is also observed among crocodiles and Komodo dragons. There is fossil evidence suggesting that Allosaurus cannibalized each other.

Tendon avulsions of the forelimbs suggest injuries to Allosaurus occurred while they held struggling prey. Injuries to the feet occurred not from running, but likely from grasping struggling animals with the feet. Such injuries suggest a diet based on active predation.

Life History

Fossil remains reveal a highest rate of growth at 15 years old, and bone deposition halted between 22 and 28 years old. Medulary bone tissue has been found in Allosaurus. This tissue is used to produce calcium for eggshells, is found in female birds, and suggests a way to identify the females of Allosaurus. Another possibility is that medulary bone found in Allosaurus might be a remnant of bone pathology.

Juveniles had longer legs compared to their adult proportions. Such a trait may have allowed different hunting strategies than they would have employed as massive adults. The total length of the shin and foot exceeded that of the thigh, allowing Allosaurus to run effectively. Juveniles may have chased down small prey. As the thigh bone thickened and widened, the muscles also became shorter. Growth slowed in the adult. These changes suggest that the legs of the adults endured significantly more stress than the juveniles.

Environment

The Jurassic Period is from 201.3-145 mya, and began after the Jurassic-Triassic extinction event. The supercontinent Pangaea rifted into Laurasia and Gondwana. The North Atlantic opened during the Jurassic, but it wasn’t until the Cretaceous that Gondwana rifted to open the South Atlantic Oceans. The Nevadan orogeny, caused by a subduction zone, began in the mid-Jurassic. Intrusive batholiths associated with extrusive volcanoes are seen today as exposures in the Sierra Nevada Mtns. In the modern North American west, the banded and colorful remnants of the Morrison Formation are exposed in arid and often remote locales.

In the Jurassic, more coastlines formed, continental climate became more humid, and dinosaurs began to dominate the land over the descendents of Triassic crocodylomorphs. Birds evolved from theropods, crocodylians filled aquatic niches, and marine reptiles populated the oceans.

Allosaurus is found in western North America, within the Morrison Formation. The formation records semi-arid floodplains and forests which lined rivers. There were wet and dry seasons. Forests were populated by conifers, ferns, and tree ferns. Savannas were also dominated by ferns and a rare conifer called a Brachyphyllum. Allosaurus lived at the apex of the trophic levels, and is the most common theropod found in the Morrison.

The Morrison Fm. has preserved many organisms from the Jurassic. Fungi, mosses, horsetails, cycads, and ginkos grew, in addition to many species of conifers. Ray-finned fish, turtles, lizards, crocodylomorphs, pterosaurs, early mammals, and many dinosaurs lived at that time. Allosaurus is frequently buried in the same area as Apatosaurus (sauropod), Camarasaurus (sauropod), and Stegasaurus (ornithiscian). Theropods of the Morrison include Ceratosaurus, Torvosaurus, Ornitholestes. Sauropods also include Brachiosaurus and Diplodocus. Ornithscians also include Camptosaurus and Dryosaurus.

In the U.S. and Portugal theropods occupied different niches. Fossil remains and geology provide clues to how Allosaurus lived with Ceratosaurus and Torvosaurus. Ceratosaurus and Torvosaurus had thinner bodies that suggest they were built for living in the forest and underbrush around waterways. Allosaurs had longer legs and are typically associated with floodplains. Functional anatomy differed among these species, as well. Fossil evidence reveals that Allosaurus was eaten by bigger carnivores scavenging a dead Allosaurus.

Discoveries

The first recorded discovery of an Allosaurus fossil was in 1869, likely retrieved from Morrison Formation strata near Granby, CO. Leidy received the piece of tail vertebrae from F.V. Hayden who acquired the fossil secondhand. The fossil was first assigned to a European genus, but Leidy eventually assigned it to Antrodemus. In 1877, O.C. Marsh named Allosaurus fragilis. The Greek meaning of Allosaurus is ’different lizard.’ The vertebral fragments from the collection which Marsh studied had features which made the vertebrae lighter, hence the epithet, ‘fragilis’. Marsh continued to competitively collect and name theropod specimens, as did his rival E.D. Cope. In 1920, C.W. Gilmore asserted that Leidy’s Antrodemus vertebrae appeared the same as Allosaurus, therefore Antrodemus should be the accepted name. Madsen published his argument that Antrodemus was inadequately identified and named, and that Allosaurus should be the name used.

The Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry has been collected since 1927, described in 1945, and has been a focus of major academic study and collection since the 1960’s. At least 73 dinosaurs have been extracted, with at least 46 of those identified as Allosaurus fragilus. Individuals range in size from one to twelve meters long. The specimens are notably disarticulated and the circumstance of their burial in such large quantity is unresolved. Some of the explanations are that the animals got stuck in the mud, a bog, or a seep, and/or that drought brought the dinosaurs to a waterhole where they died.

In 1991, a Swiss team discovered a 95% complete, 26 ft (8 m) long Allosaurus skeleton near Shell, Wyoming. The skeleton (MOR 693) was named “Big Al.” “Big Al” has received considerable popular recognition. The Swiss team also discovered one of the best preserved specimens of Allosaurus. They found it in 1996 and nicknamed it “Big Al Two.” “Big Al”, described by Breithaupt, had 19 bones with pathology such as breaks and bones infections (osteomyelitis).

Taxonomy

The taxonomy of the Allosaurus genus is very complicated due to the fragmentary nature of the type specimen (A. fragilis). In 1877, O.C. Marsh described the first known fossils of this genus, though the fossils were called Antrodemus. Before 1976, publications described Allosaurus as Megalauridae and Antrodremus. Many other theropod dinosaurs were assigned to Allosauridae and have since been moved to different families. A petition was submitted in 2010 to have A. fragilis transferred to a more complete, neotype specimen.

Allosaurus is a carnosaur, which is a separate branch of theropods from the tyrannosaurids. Tyrannosaurids belong to Coelosauria. Allosauridae has the fewest members of the four families within Carnosauridae. Members include Allosaurus, Saurophaganax (which may be an Allosaurus), and possibly members of the genus, Epanterias. Some scientists assert that Epanterias is a member of Allosauridae, but Saurophaganax belongs in a separate genus.

Since 1988, seven species have been asserted as most correctly belonging to Allosaurus, as well as ten more which are assigned but their placement is contested. Most assignments to Allosaurs have been contested, a situation caused by the meager example of bones associated with the type specimen. In addition, other genera have been added to Allosaurus. These classifications have made Allosaurus somewhat of a catch-all for Allosaurus-like, tetanuran theropods. Tetanurae was proposed by J. Gauthier, in 1986. Members of Tetanurae appear in the early to middle Jurassic, and include Carnosauridae and Coelosauridae, and they share closer relationships to birds than to Ceratosaurus.

The most common Allosaurus found in the Upper Jurassic of North America is A. fragilis. Other species that have been discovered from the same formation are A. maximus and A. jimmadseni. Scientists have debated whether the only two described species of the Morrison are A. fragilis and the taxonomically disputed, A. atrox. The possibility remains that Allosaurus in the Morrison includes only one species and individual variation explains the differences observed among specimens. Skulls from the Cleveland-Lloyd quarry have revealed that species distinction based on lacrimal horns and jugal shape may be an incorrect approach.

There are other notable members of Allosaurus which are outside of North America. Allosaurus europaeus was discovered in Late Jurassic sediments of western Portugal. This species may also be A. fragilis. A large theropod, possibly a basal tetanuran or carcharodontosaurid, is found in Tanzania and is classified as A. tendagurensis.

Reviews

Reviews